He has looked with favor on the humble condition of His servant. Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed.

– Luke 1:48

Section One (Parsha Debrief):

This week’s parsha Text contained: the birth of Esau and Jacob, Esau trading his birthright, Isaac’s sister, a bunch of wells, and a story of deception and blessing.

For those unfamiliar, there are three main patriarchs of the Jewish faith: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. To date, we’ve talked extensively about Abraham and why God chose to partner with him. This week we are introduced to Jacob, whom all of the tribes of Israel come from. But, what about Isaac… what’s his big moment?

Rabbis still wrestle with that question. (below we use Aleph Beta’s understanding)

Here’s the thing, there aren’t many. Even though Isaac is mentioned a ton in this week’s parsha… are the stories really about him?

In the Midweek Reading Guide, we pointed out how weird it is that the generations of Isaac were Abraham fathered Isaac. This isn’t the first time the Text fails to directly follow that statement with biological generations. In fact, it’s often less about offspring and more about legacy. Rabbi David Fohrman suggests, when this is the case, the Text is trying to tell us that the legacy of ___ is not what we may think. If true, what does the Text want us to learn when it implies Isaac’s legacy is that he’s the son of Abraham?

We know that Abraham’s partnership with God needs to be passed on. Continuing the Mission of God that Abraham initiated is contingent upon how the first heir responds. Isaac’s decisions and character can squander or sustain the partnership and mission.

That’s his legacy — to be a responsible heir. It’s not an easy one.

Can he keep the vision alive?

The only story actually about Isaac in our parsha Text is the digging of wells. This seems like an unlikely place to learn about Isaac’s character and mission status.

Like Abraham, the Lord blessed Isaac with all the things one would need to be a blessing to the world.

Isaac sows and reaps 100-fold 😉 😉 because of the Lord’s blessing. Then, the Text says the man waxed greatly, grew and become very great. Here’s how I read this — God blesses Isaac. Immediately after, Isaac continues to acquire and accumulate.

Isaac becomes super rich. And, the Philistines (whose land he is occupying) become jealous of him (Genesis 26:14). This is the first time in scripture qana’, a word for jealous, shows up. Some translations say envious, so it is easy to think the Philistines want what Isaac has. But, qana’ is actually more of a zealousness. In fact, God ends up using the exact same word to describe Pinchas’ zealousness in Numbers 25:11,13 (which we’ll get to unpack in 2019). The Philistines are upset and want justice.

Which is important to note because Abraham found himself in a similar situation last week with the Hittites in the land of Canaan — with a very different outcome (Genesis 23:6).

Still, we can easily say jealousy is the evil, and Isaac did nothing wrong.

But, the wells tell us otherwise.

Isaac starts re-digging the wells of his father, Abraham (footnote #1).

The first well he tries to re-dig is quarreled over by the local shepherds (Genesis 26:20). The second well he tries to re-dig is also contested (Genesis 26:21). But, no one fought him over the third re-dug well. Why?

Did anything change between wells 2 and 3?

Yes. He moved from there (Genesis 26:22). Was it as simple as moving? Kind of. The only two times `athaq (to move) is used in all of Torah is here, and regarding Abraham in Genesis 12:8.

When Isaac started looking like and acting like his father, no one contested the well. Isaac changed between wells two and three.

All these wells were Isaac’s way of showing ownership of the land in Gerar (footnote #2). But, God never asked him to own land. Quite the opposite, God uses a completely different word to tell Isaac to live in the land as a foreigner (Genesis 26:2-3).

We’ve heard that idea before. Abraham recognized he was a foreigner in the land of Canaan in last week’s Text (Genesis 23:4). And, instead of jealousy, resentment, and rejection, the Hittites said to Abraham, “you are God’s chosen one among us (Genesis 23:6).”

At the start of the wells story, Isaac is trying to own everything. By the end, he recognizes his role is not to force the mission. Force isn’t a positive way to influence. So, Isaac stops trying to mark his territory.

After, even though the third well was successfully dug, Isaac continues to Beer-sheba. He isn’t’ focused on building an empire any longer. His legacy is different. So, God responds with a repeat of the initial promise but this time without mention of land. Because, now Isaac gets it. The land is not, and was not, about ownership — it’s tool to bless all nations.

And, just like his dad, Isaac immediately takes on a new posture:

The blessing is being a blessing!

Section Two (Connection to NT + haftarah):

Our Luke Text enters the Jesus birth narrative this week. In it, we are told about the prediction of Jesus’ conception, and invited into the interaction between the NTs two main matriarchs; Elizabeth and Mary. The matriarch’s are the center of attention in this section of Luke. In fact, one third of the verses in this section of Luke Text are devoted to Mary’s Magnificat.

Scholars suggest that Mary’s words echo Hannah’s in 1 Samuel 2:1-10. What do you think?

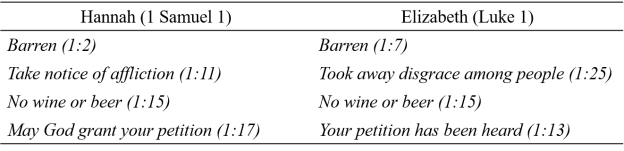

I think there’s more going on. I think Hannah’s plight and story are closely paralleled by Elizabeth’s.

But, here’s the odd thing, Hannah also says, may your servant find favor with you (1 Samuel 1:18). The angel, Gabriel, says this exact thing of Mary, not Elizabeth (Luke 1:28,30).

Are Elizabeth and Mary somehow both connected to Hannah?

Furthermore, last week we suggested, that Mary might, in some way parallel Rebekah. This week’s Luke Text describes Mary as a virgin (parthenos in Greek). This is the only time the author of Luke uses this word (Luke 1:27). Parthenos shows up in the Genesis section of the Septuagint six times. Five of those are in one story — a story we already discussed — in which Eliezer journeys to find Rebekah. The Text makes specific reference to Rebekah as a virgin.

Also, in the Septuagint, the transliterated Greek word skirtao (to skip or leap), only shows up once in all of Torah — Genesis 25:22. Here, the children inside of Rebekah leaped with each other. Skirtao only shows up three times in all of the NT. Two of those three times are in our Luke Text when the baby leaps inside of Elizabeth at the sound of Mary’s voice (Luke 1:41,44).

Are Elizabeth and Mary somehow both connected to Rebekah?

There’s more, the connections even continue to Leah and Rachel (Jacob’s wives) in next week’s parsha.

I think it’s safe to say, the matriarchal story is somehow one big story, not isolated, individual incidents.

And, it doesn’t surprise me at all that the author of Luke is trying to unify the women of the Text!

Section Three (missing the mark):

I think many pastors want to put the Christ back in Christmas. But, even with that good intention, many still fall short because they wait too long to try and influence their church body. Kind of like Lot.

You can’t wait until advent is knocking on your door to model the Jesus birth narrative. As a pastor, you have to recognize that the world around your congregation has been shaping Christmas since the end of October. And, that the world around them has been shaping their worth and value all day, every day.

By advent, the good life has already taken root.

And now, commercialization owns more and more of the Jesus birth narrative.

In contrast, Isaiah speaks to the king of Judah, in our haftarah Text, saying that a virgin will conceive, have a son, and name him Immanuel (Isaiah 7). The Matthew Text from last week is keen to note what Immanuel means, God with us (Matthew 1:23).

But, are we with God?

Maybe that’s a question pastors need to ask themselves regularly (footnote #3).

Because, at the time of this post, Halloween just wrapped up and advent calendars are already for sale.

Section Four (real-world applications):

We skipped over something important regarding Isaac.

“Isaac prayed to the Lord on behalf of his wife because she was barren. The Lord heard his prayer, and his wife Rebekah conceived.”

– Genesis 25:21

Also, the angel that spoke to Zechariah in the Luke Text last week said, your prayer has been heard, your wife Elizabeth will bear you a son (Luke 1:13).

Two men. Separated by ~1,700 years. Both entreating on behalf of their wives.

Like intercession, entreating prayer is real-world application worthy!

What can we learn?

First and foremost, prayer isn’t prescriptive. We can’t pray what someone prays in the Bible and anticipate or, worst yet, demand the same results. I recognize folks have made a lot of money writing books based on prayers in the Text. I don’t think that’s why we see prayer in the Text.

So, why do we pray? Aleph Beta has some excellent resources to help unpack that question.

The Rabbis say, one reason we see prayer in the Text is because God desires prayer. In fact, it might be better to just hear it straight from the mouth of a Rabbi.

“[F]or Creation to be truly alive, it needs prayer. Not the rote, ritualistic kind of prayer; but prayer that’s part of an active, caring relationship between the world and its Creator. The reason God listens to prayer, is because woven into the very fabric of Creation, is God’s desire to be in relationship with people, even with us, even today – and prayer is the way we engage in that relationship. It’s about leaning into our relationship with God, bearing our hearts in an intimate dialogue, and living in an authentic, dynamic relationship with our Creator.”

– Imu Shalev, Aleph Beta

Sit with that for a moment before continuing on.

I find it Interesting that Jesus echos an ancient prayer (i.e. Amidah) when He models prayer for His disciples. It’s focused on bringing Heaven crashing into earth.

What if, when we pray, we bring a piece of Heaven on earth.

Think about it. If prayer is an avenue to be in authentic, dynamic relationship with our Creator — we should leave that space having experienced Heaven.

I would guess that anyone who experiences just a piece of Heaven would carry some of that with them into how they engage and interact with the world around them.

By entreating, we bear our hearts to the Creator regarding the petitions of loved ones. We return with pieces of Heaven.

Here’s the deal, we aren’t told the words Isaac or Zechariah prayed. Just the heart behind their prayer. It was for and about their wives, not themselves.

I know a husband who sets an alarm on his phone for multiple times throughout the day. When it goes off, he stops whatever he is doing and prays on behalf of his wife. He drags Heaven with him wherever he goes!

May we lean into our relationship with God, bear our hearts, and experience authentic relationship with our Creator.

May we seek the Lord and raise petitions on behalf of our spouses.

Next Week’s Readings: Genesis 28:10-32:2; Luke 1:57-80

- Isn’t that interesting? Isaac’s legacy is somehow wrapped up in being Abraham’s son and the one story that focuses on Isaac (not his sons) is about re-doing something his father did?

- Jewish law ends up discussing that only owners can alter the landscape. Digging a well seems like the landscape is getting altered.

- Thankfully some pastors have wrestled with that question. I recommend learning from them as you prepare for and participate in advent this year. The first must see advent series is A Tale of Two Kingdoms. The second, Emmanuel: God with us.

2 thoughts on “The Shuvah Project #8 — Matriarchs and Patriarchs”